The History of Women Stitching, Ep. 5-The Hard Truth About Samplers

Sally Follansbee’s 1787 sampler from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

It is finally happening, we are going to talk about the Industrial Revolution…sort of.

Since the beginning of this series, The History of Women Stitching, available as a podcast or blogpost with some great images of art and links to articles and books, I have emphasized the pivotal nature of invention, as in when in prehistoric times we discovered we could roll fiber upon itself by using a simple drop spindle and create continuous thread which led to weaving and cloth production. The move from animals skins to cloth was evolutionary. More recently, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution was evolutionary as well- when at first through harnessing the power of flowing water- hydro electric - and then steam- men invented machinery to automate what had been done since the beginning of time by hand or under the power of animals- grind flour, process ore, produce steel as well as power trains, farm equipment, the list goes on, but… mic drop time- that also started with the production of cloth when weaving was automated in England around 1760. Yup the manly Industrial Revolution of steel production started with the womanly need for fabric. Don’t be too impressed because weaving also allowed a man to step on the moon and there to be computers, but that is another podcast.

In the mid 18th century, the desire for more fabric consumption around the world in trade and the need of efficiency in making it started the age of many an invention in automation. Yes, commerce is what makes the world go round. Interestingly weaving machines were invented first and put quite an urgency for the still hand spun thread needed to thread the machines. But mass production of spinning was a harder nut to crack then the automation of weaving. Multiple pieces and parts were needed to be invented to achieve automation in spinning with the invention of the spinning jenny happening in 1764 by Lancashire cottage spinner James Hargreaves. What did he get for his efforts? His neighbors came in and smashed his multi spindle at once spinning wheel due the outrage of their loss of their livelihood which would continue and change the very fabric of well….everything.

Rightly so, many were not happy about their loss of work because of the new advancement in technology when one worker operating the spinning jenny could produce one hundred and twenty spools of thread in the time a spinner could spin one spool with a spinning wheel. Livelihoods of the rural spinners and weavers were being lost to mass production.

The first or at least most legendary protester of this loss of income was a weaver named Ned Ludd and under his instigation there was destruction of weaving mills and riots and then trials executions and penal transportation, ie the rioters getting shipped off to Australia. No one was going to stop the advancement of technologies that put more money in the pockets of a few. We still refer to those who do not like the advancement of technology or not like being replaced by technology as luddites.

I write this the day after the “big beautiful bill” was passed by congress and the day before our country celebrates its 249th birthday, and there are declarations of deporting troublemakers whether they are legally US citizens or not. Folks, there is nothing new under the sun.

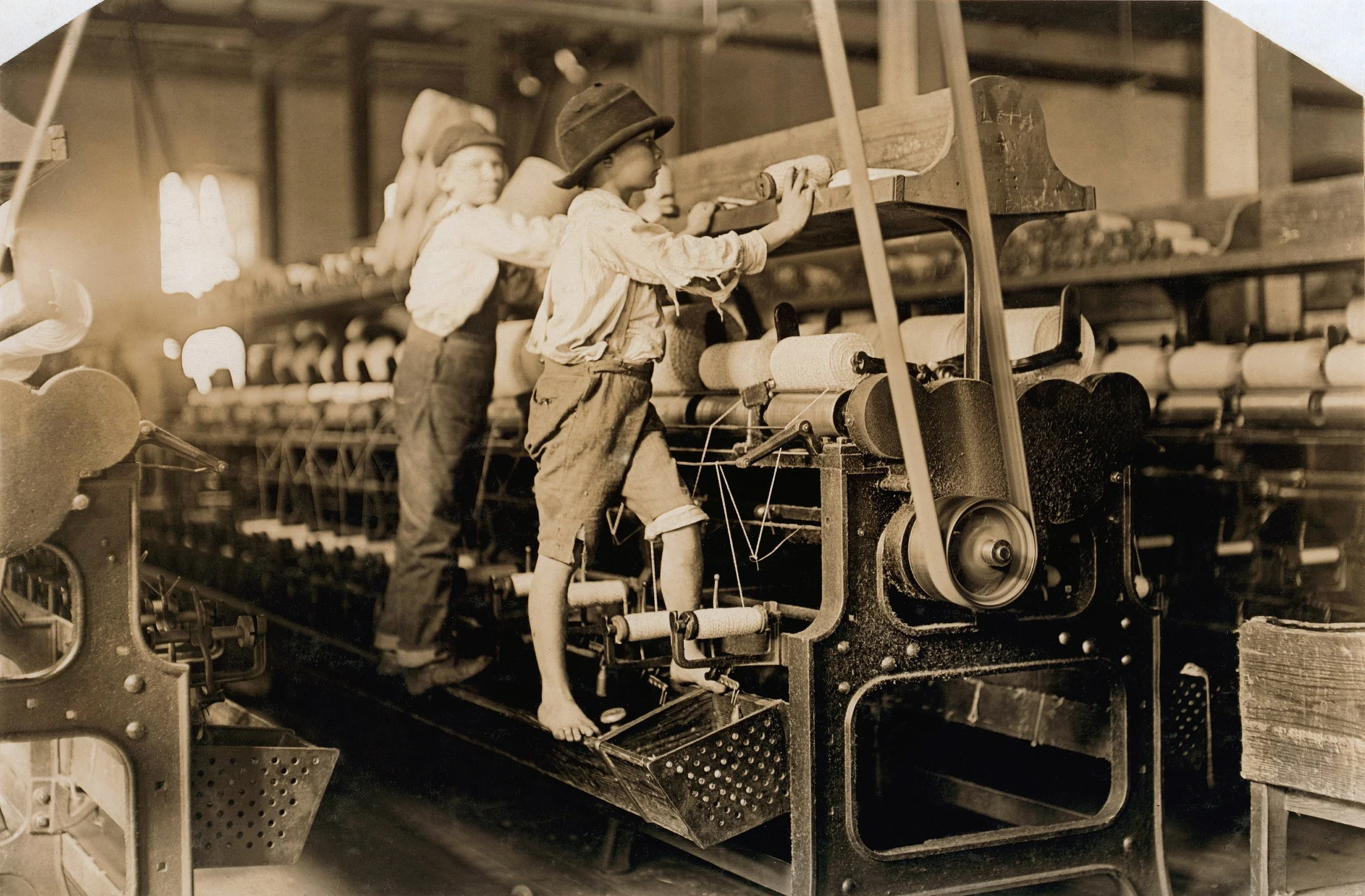

But in the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution pulled families from a rural way of life where they had their own autonym of farming and control of their cottage industries like weaving and spinning to a miserable urban setting were the factories stood polluting the air, water and ground around them and greatly lowering their quality of life. It is estimated that in 1750, 80% people lived in rural England and 20% lived in urban cities. That entirely flipped in the first hundred years of the Industrial Revolution when in 1850 80% of the population lived in the cities and only 20% could make a living in the country. Under the factory system, everyone in the families were pulled from the home to work in the factories where often the smaller hands of the women and children were needed to reach in to parts of the machinery. Check out THIS article on the Historic England Blog.

All this broke the time honored tradition of seasonal rural labor and traditional division between the spouses and child rearing that had existed for a few thousands of years. Now, across Industrialized Europe and the northern states of the US the majority of people lived their lives in cities on the demands of the few- the owners of the factories who provided subpar housing and horrid working conditions- all fodder for tales like Oliver Twist ( 1837) by Charles Dickens …

and The Little Match Girl (1846) by Hans Christian Andersen

What else did the Industrial Revolution give us? The Arts and Crafts movement for one, as a direct reaction to the mechanically produced products that once were created by hand. Think William Morris’s (1834-1896) luscious fabrics…

But designers like William Morris needed a place to sell their handcrafted work and men like Arthur Lasenbury Liberty (1843-1917)

promoted and featured artisans and designers like Morris in his department store. Of course one of my favorite and long running shows- Time Team has many episodes on the Industrial Revolution, like season 10 episode 6, where they dig up one of Arthur Lasenbury Liberty’s mills and show how the fabric stamping tradition of India was stolen (another podcast) and attempts were made to produce the “oriental fabric” in England.

Many stitchers today when visiting England today make a pilgrimage to the still in operation Liberty department store situated in a Tudor-esque building in East London.

In my last podcast, I mentioned the TV docu-series Britian’s Most Historic Towns where Dr. Alice Roberts highlights Belfast with its linen productions as the most Victorian Town. She also does a great job bringing an understanding to the inhuman conditions those working in the weaving mills were forced to live in and how eventually some reform came to the working class with labor laws, better working and living conditions and a limit to the work week.

Two episodes ago we talked about how different the working class and privileged classes did their laundry and how there was a need for the well off to keep track of all their linen by having it all- bedsheets, bath towels, undergarment, table clothes, napkins monogramed before it was sent out, no matter how far to be laundered. With the advent of steam automation and chemical whiteners in the Industrial Revolution well to do households still needed someone to stitch monograms on everything they owned. But even if you were only in “trade” , the middle class had much opportunity to rise in importance during this time and your linen did not travel that far, maybe only to the back of your country estate or to the mews behind your townhouse, one might think you were wealthier than you really were if everything they saw in your house and person was monogrammed. Monogramming your family’s initials could be done for practical reasons and for vanity, a word we will get to.

This was also a time when tea towels, tablecloths, bath towels could come by the yardage from the linen and cotton mill and then it would be cut and hemmed to the desired lengths. A great example of that is the Carl Larsson’s ( Swedish, 1853-1919 ) " Sewing Girl " ( 1911 ) on my moonflower studio blog post. Laura Ingalls Wilder was a hired girl to do the stitching of more well to do town’s folk.

Also in a time of no fast fashion, wealthy or not, there was a lot of altering, mending or darning. Who was doing that mending?

My great grandmother had twelve children, six girls and six boys. My grandmother told me many tales of her mother taking a dress worn by an older sister that her mother altered and sized down for her. News flash, yes, women were smaller than we are today because of nutrition, but also dresses that have survived often started out a larger size and were altered to get the most use out of them. The question is by whom?

I guess the point I am trying to make it, this was a time even in an era of automation that there was a great need for skilled hand sewers so therefore girls whether rich or poor were instructed in the skill of stitching. How did those doing the mending, the altering, the monogramming know what to stitch…. that would be the samplers.

Sampler- defined by google as…

a piece of embroidery worked in various stitches as a specimen of skill, typically containing the alphabet and some mottoes- and I would add motifs.

The important phrase there is “collection”. I tried to knit a sampler blanket with multiple different stitches, moss stitch, herringbone, cable, to learn the different stitches. I didn’t finish the blanket, but I did learn how to stitch a lot of different knitting patterns.

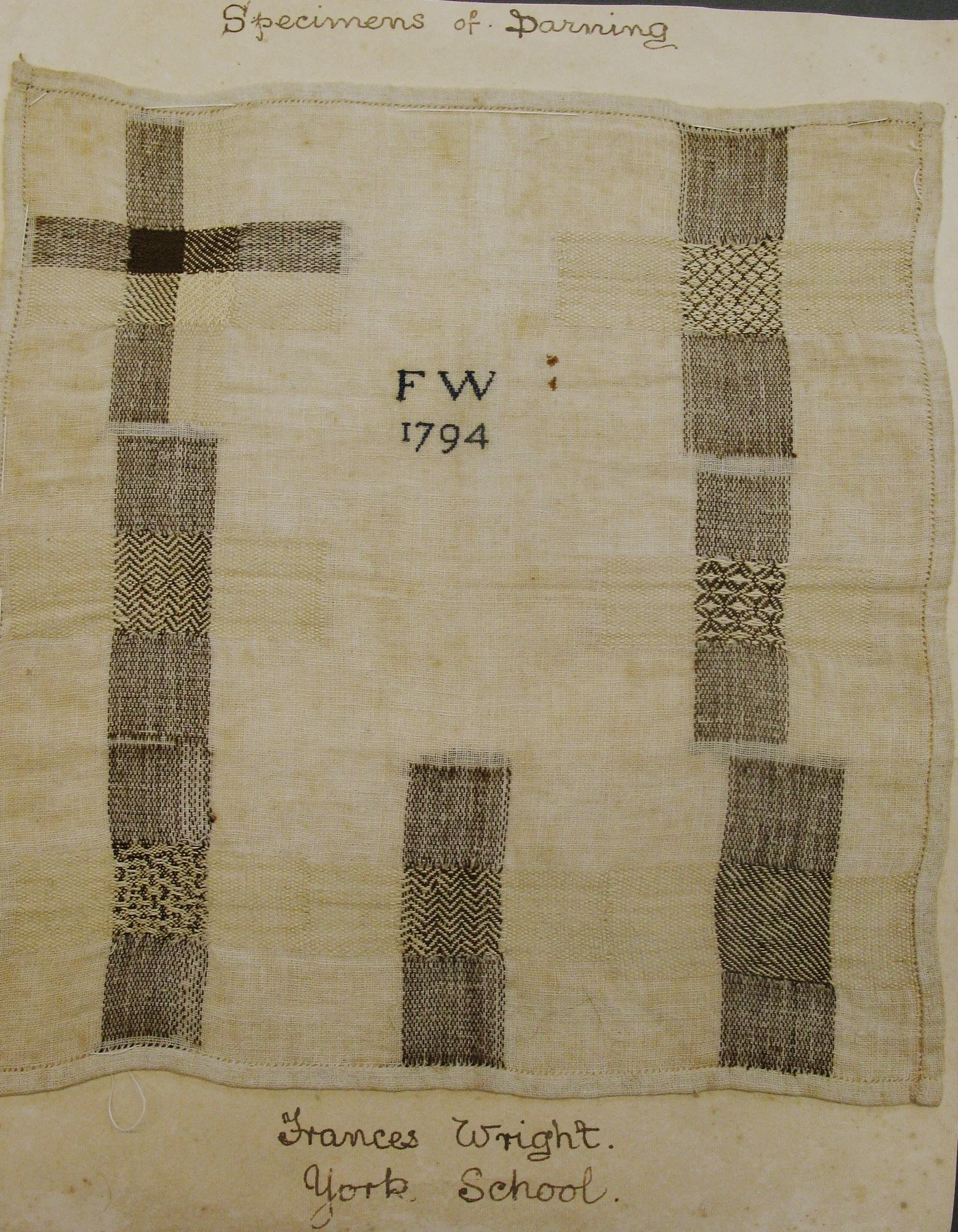

On the blog post I put up a images of Francis Wright’s “specimens of darning” sample stitching from the Quaker’s York School from 1794, showing her practicing seven different patterns of darning stitches…

I found it on Wikipedia Commons and let me quote from the page…

“York School (1785-1814) was the forerunner of the Mount School, York, which opened in 1831, and is still currently operated by the Society of Friends. The schools were established in response to the educational and religious needs of less fortunate children. A “guarded education” was stressed in the school’s prospectus, and the girls were taught “accomplishments”, including sampler making. and a sampler of darning was both a record of patterns and techniques and a diploma of accomplishment.

We will get back to why girls and minorities schooling often had phrases like “ a guarded education” on another podcast but…

I could look at Frances Wright’s darning sampler and follow her stitches and repair my own damaged linens with one of her patterns, a blown up image on my website…

from wikipedia commons

Just like I could choice between two styles of the Alphabet from another true sampler on my website…

From their website…

From the Public schools established in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1836, and needlework and sampler making were part of the curriculum. After grade three, the girls and boys where separated and went to different schools. For the girls, one afternoon each week was devoted to needlework. There are samplers in existence from School No. 7 and School No. 8. It is thought this work was done under the tutelage of Miss Fanny Webber, who taught from 1836 to 1863. M. A. Hofman has not yet been identified.

I could also do a rant on how Carlisle Pennsylvania was the epa center for the Indian School taking tribal children from arms of their parents sometime at gunpoint from reservations in the west and shipping them to Indian School in the East to give them an education , punishing them for speaking their language and training them to be domestic servants… but that is also another post and I do not know if this sampler is from the Indian School, white girls also were indoctrinated into a lifestyle they had very little choice in… back to that phrase “guarded education”.

But however wisely or unwisely done, there were many benevolent organizations or individuals that took it upon themselves to train girls in the skill of stitching to better their lives or make them less of a hinderance and more of an asset to their societies. The Royal School of Needlework ( United Kingdom) was just such a school/studio….

It’s current patron is Queen Camilla and its embroiders stitched some of the wonderful banners and garments for King Charles II coronation and did stitch work on the current Princess of Wales wedding gown.

At its basic basic idea- a sampler’s purpose it to teach new stitching skills, show examples of stitches that can be used and to show one’s abilities in stitching like a resume. They are practice pieces. Different alphabets were presented in these “working samplers”, different styles to be used probably mostly for stitching the monograms on all the linens and clothing for laundry purposes by a hired girl or servant.

But samplers are also full of nonsense placements of animals, birds, flower in urns, trees and house, with very little regard for size. These are ”motif”, which google.com defines as -a decorative design or pattern.

Below or on my website- is a wonderful example of a stitched sampler of different motifs.

from wikipedia commons

So why the huge animals floating above the small house, what is the meaning? There probably is not a great purpose or a hidden reason why the bird in the tree is huge and the other motifs in the sampler above are smaller and of different styles.

Why do I think this, well, In art school we were encourage to do the same, in our studies, in sketching, fill a page with our work, filling in all the clean available spaces before we turned the page to a new sheet, sometimes even turning the sketchbook upside down to have a better angle to draw what we were looking at or even to draw over an existing motif to finish an idea…

from HERE

Leonardo Da Vinci was taught the same and probably in his time not to waste paper. On my blog post-there is his sketch with very large horse head centered on the page -very well executed, probably the first thing he drew, but then his attention shifted to the legs, and so in a corner he twice sketches a close up of the horses legs in movement. Then he did some simpler side view of the beasts, but then a boy and an old man caught his eye, maybe in preparation for a larger work. This is what we could call a “working sketch”, not intended to be framed or to be the end result, just a piece of paper working out ideas or simply practicing.

And that is how most samplers should be looked at, not one well planned out design that was purposefully placed on one piece of linen or cotton, but a multitude of little designs, alphabets and motifs stitched where there was room to stitch them. Perhaps the gigantic pheasant floating above the Georgian house has no other great meaning than there was room to stitch a pheasant above the house. Perhaps the floating motifs, the crammed in alphabet was more to do with economy of space and materials in a teaching or working stitched sample than anything to do with cultural style.

Cost of materials is something that is not thought much about today. Women have crafts rooms bursting with fabrics, threads, patterns they might never get to. That has not always been the case and we will get to that in a bit but both schools for the poor and wealthy or middle class did not have unlimited accesses to resources especially in the United states from its conception through the Industrial Revolution where fabric and floss had to be imported from other countries and pesky wars, there were a lot of wars across the globe could interfere with the obtainment of favored supplies, let alone the high cost of those supplies.

But why are there more girl samplers around than more thought out stitched pieces like the lovely cross stitch of a girl and her doll near a pond, with a bridge, surrounded by ornate trees, think “little women” I have posted on my blog"?

A lot of girls were introduced to stitching, took some sort of sampler class at home or in a school whether that school was established or simply an older governess attempt to have an income by teaching stitching in their own homes.

from wikipedia common

From wikipedia commons…

Sampler made by Elizabeth Stine in 1803 in Harrisburgh, Pennsylvania. It was created under the guidance of Mrs. Leah Bratton, also known as Leah Galligher or Leah Meguier, a well known girls schoolteacher in Pennsylvania in the 1790s to 1820s.

Bit not all of those girls finished their samplers or were skilled enough or had the desire to stitch more. How many started craft projects do you have in your house? Did you or your daughters try knitting, crocheting, macrame and not finish? What would an archeologist surmise about our culture by your unfinished projects.

But what of the samplers and more advanced stitch work found in well to do families of the middle class and gentry that were framed or even listed in some families wills, declaring the girl’s work would stay with the girl’s families instead of decorating her new home? Of course some girls did have an aptitude for stitching and did their families proud, like Martha E. Rust (1822). From Wikipedia…

A young girl typically began with a basic sampler to learn stitching technique and then progressed to more complex, embroidered pictures as her skill level increased. This cross stitched cornucopia picture was probably Martha’s second needlework sampler. Martha was born in 1808, one of seven children of John and Elizabeth Rust. The Rusts were a prominent family in northern Virginia, and could afford to send their daughter to Upperville Academy, run by Rev. John L. Dagg, a leading Baptist theologian. Martha had not quite attained her 15th birthday, when she was married to Daniel Sowers, age 21, on January 16, 1823. She died in 1825, at age 17.

Why, oh Mr. Darcy, do girls have to be accomplished at all? And It is amazing how far in this podcast I have gotten and not mentioned the middle class!

The answer to that would be vanity. Something we have been talk about but nor really labeling since literally the beginning of time or at least the first podcast of the Kelly Lewis Podcast and the first podcast of The History of Women Stitching, just good ol’ vanity.

May I bring back the venus figures and the realization of continues thread can be used for adornment? Pic up on my blogpost but be warned they are well endowed rock carving of faceless women, but with ornate head and apron decorations…

Nothing has changed in a few thousand years or a few hundred thousand years, we still want others to look at us and well envy us.

I talked about it again in episode 2 with the painting of William Brooks family displaying all the expensive and glorious spices and game animals they could indulge in 16th century England when the Tudors and other great powers were sailing the globe for riches and exotic indulgences…

from HERE

Vanity was why the privilaged linens had to be the whitest white though natural linen is actually rather a grey white and the richest of the rich sailed them across the globe to whiten them. That would be in episode 3.

Now one has to be rather rich to hire a classical trained artist to paint your family as grand as Sir Williams Brooks in all your finery or wait six months to get your laundry back from the south seas. But there were other ways the not so fortunate but still well off broadcast the wealth they did have and it is actually called vanity art or at least that is what my art history professor called it, not Professor Dare but Professor Vogel and even if the quality of vanity art went down with how much a family could afford it could be still “wonderful” - a word Professor Vogel loved to use- in comparison to your neighbors, because vanity art screams “Look what I have!”

While the well to do in America like the Washingtons and the Jeffersons could afford the best, the middle class relied on itinerant artist…

that traveled the country and for a fee and room and board painted folk arty paintings of your family, your house, your land, your barn, your prized steed, bull, or hog…

from HERE

From Picturing the Farms of Ohio and Pennsylvania in the Late 18th Century article…

For a small price, Ferdinand Brader would draw a bird’s-eye view of someone’s homestead.

check out my blog to see some examples of itinerant artist’s simple illustrations of Americana in the 19th century..

from HERE

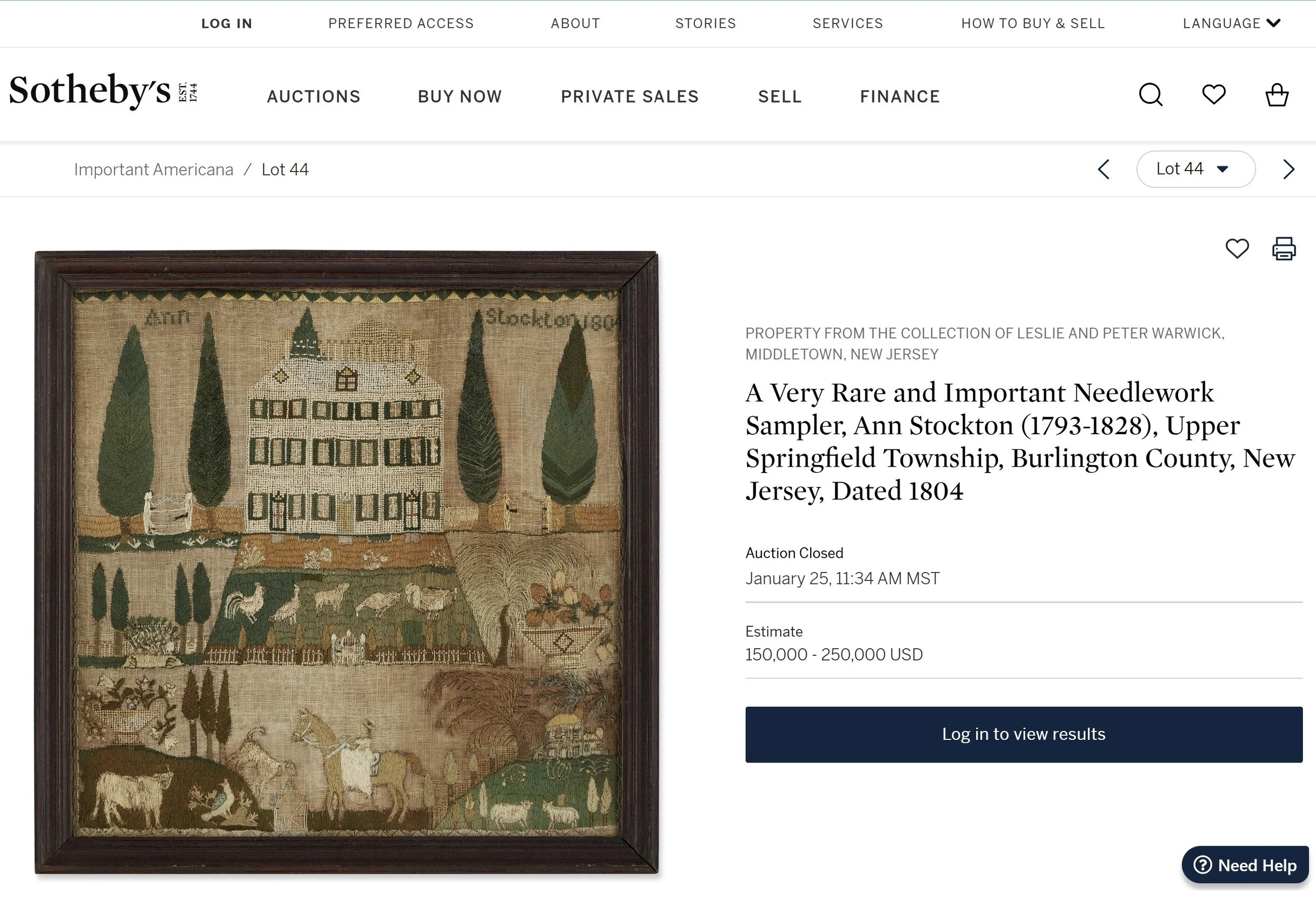

especially the very simplistic view of a farm in Mahantango Valley that almost looks stitched. You know what is even more economicl then giving coin to a traveling artist that might partake more of your food and drink than you like? A daughter that could stitch a sampler showing the wealth of your family, the abundance of your farm. And by the 19th centuries we also had pattern books and retired school teachers, governoresses and unmarried ladies that could take on the supervision of creating such a stitched vanity piece showing your families wealth. One sold at Sotheby’s the first of this year with an estimate between $150,00 and $250,00 us.

from HERE

The similarities of the itinerant artist paintings of farms in 19th c. New England and Ann Stockton’s stitching, screen shot up on my blog post are remarkable.

However the sampler craze started, and I admit I am guessing about the vanity aspect of daughter stitching work to appluad their family’s wealth along with other stitching we have to record baptism, death, marriages and family trees- all work that a family might also ask an itinerant artist to immortalize and whether these fancy document of life are painted or stitched- they are also very very similar.

But how did girls whether under the instruction of their mothers, governesses or teachers who were not so artistically talented do it… that would be pattern books. Go back to the motifs and alphabets covering willy nilly like Leonaro Da Vinci’s sketchbook page. They could be actually stitched samples for the girls to choice from to match their own Georgian style farm or townhouse, the kinds of trees they had in their yards, the kind of carriages, fences, animals that had connection to their families or add appropriate motifs to family trees, birth death or marriage record. But when printing became cheap and available they could get their motifs, alphabets out of pattern books.

Now, one might be thinking, who am I to declare that the motivation of all of this from my viewpoint is just simple vanity. Reality is in the four years of art school, Professor Vogel had only one reference to share on women’s work and sadly or poetically it is out of print now…

A collection of woman’s work, mostly stitching done by young girls and older matrons, accompanied by snippets of diary accounts pondering such things as how tall their future husbands would be and how many stitches it will take to make their jackets.

Today, these samplers that usual have no context, no provanance, no recorded information other than the name of a girl, her age, possible a date, place or instructor listed are a hot item and are searched out, auctioned, framed or reproduced and are used to make conclusions of our great and great great and farther back grandmother’s lives and that terrifies me.

The most important conclusion I get reading the diary accounts of our forbearers, is that we should not conclude what life was like for these women from what they were able to do as girls and how much other factors dictated what they did do. How cute or sweet a finished stitching is, the sentiment of the phrase has no barring on who stitched it. Was it to their liking or were they forced to stitch for hours as a lesson or penitence. We simple can not know and diary accounts can not be totally trusted either in a time women would not even write about their romances, pregnancies, losses of babies, hard marriages, struggles in their private notes.

What if all we had of Da Vinci was his random willy nilly sketchbook pages. What if we did not have his great works of art and drew our conclusions of his intent, from just a mismatched random layout of motifs? That is the problem with girl samplers. We do not have much to draw conclusions from and we draw too broad on what we do have.

Was there a Da Vinci level artist amongst the girls in the last few hundred years? Yeah, probably a few actually. How women have been regulated to craft, to expected motifs and style of what cant be called art because it is not independent not from their own creativity is a subject I will always be talking about and highlight those amazing women artists who were brave enough to do their own thing. But the women who did not- the girls who were instructed in stitching and told what to stitch- they need to be applaud as well, their work is amazing, a illustration and sometimes the only document of their place in our history. To often reading the description of a sampler in a museum, only the women’s name and possible date of birth is given and then the research focuses on her husband, sometime his occupation and family- what can be found in the archives. That is like finding a Da Vinci and then talking about his wife, her family etc. but Di Vinci did not have a wife so lets say…. Monet and then listing all the info about his wife… whose name was Camille if you are wondering and he painted her often…

But that is the lot for women. Our history often slips over to someone else history, mainly our husbands and girl samplers are sadly one of the few things we do have. And well they are being erased from the records. Okay that is a little dramatic, a little.

Today in 2025 there is a new interest in samplers, cross stitch samplers and that is great. Many are preserved and archived in museums, being found by antique dealers and in auctions rather cheaply. Many are being found and proudly and careful displayed by stitchers, a bit of history on their walls of their homes. Some are found and reproduced by cross stitch designers and then those patterns are available for others to stitch as replicas and some of these are absolutely gorgeous.

But not all these hundred year old plus samplers get the treatment and respect they should being one of the few documented artifacts we have as women of our history. How do I know? I’ve seen, via youtube some redesigners treat 100 year old samplers in ways that would make a museum conservator cry and well me too. Everything attached to these girl sampler help tell us where they came from. The frame, the backing of the frame- all need to be examined and record somewhere. I have seen these re designers hold up hundred year old sampler by the edges in the air to show the stitches closer, I have seen them lay the hundred year old stitching on the table or on the floor and then, pile other work on top of it and have a cup of coffee sitting there.

Obviously more samplers are handled away from the recordings of youtube. But those that have recorded their handling of these samplers make me cringe. What would I want to see? Them carefully recording by photo every step in removing the samplers from the frames. Recording any labels, backing etc. and saving any documentation of where by whom these samplers were bought or auctioned. Then mostly take a high resolution photo of the samplers, which could show the stitches for making a new pattern much easier and then archiving the original sampler in archival tissue paper and boxes with all the identifiable labels, the backing it came with or having it archival framed by a professional. I do know there are some data bases for antique quilts, there probably are also for samplers where documentation including photographs could be upload and compared, back to the multiple pattern books they all utilized.

I am by no means saying the samplers should not be re charted and released if there is interest in them, just not bought, removed from their frames, their connection to their past with out record and then not handled with the upmost care while they are reproduced and a high res photo would do that.

But there has always been such a disposable idea to women’s craft, we will dive into that next time when we talk about how the Industrial Revolution along with advancement in chemistry gave us cheaper fabrics and dyes as in a rainbow of colors and with the advancement of cheap printing changed how we women could stitch for our livelihood or chose to stitch in leisure time. Until then listen to my rant on how Craft is Not a Four Letter Word but Art Is or the other episodes in this series and have a wonderful 4th of July weekend with those you love.